Productivity is a positive sum game

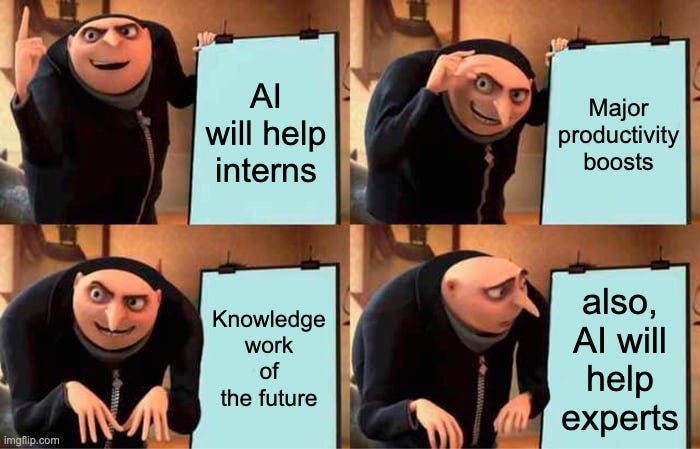

Who are those to benefit the most with AI in the workplace? Experts? Newcomers?

The flashy headlines asking if AI is coming for your job might sell newspapers (or generate clicks), but they miss a deeper story: how AI is transforming the way we work, often in ways we don’t expect. For example, the prevailing narrative says AI tools are democratizing productivity, giving novices a boost to compete with seasoned professionals. But are the inexperienced the only ones that stand to gain from AI assistants?

Experts for the win

I decided I wanted to write this after reading this paper from Aidan Toner-Rodgers at MIT. It studied how a tool powered by advanced AI algorithms, could support researchers in discovering new materials. This tool acted like a digital assistant, generating suggestions for potential combinations that scientists could test. The scientists using AI achieved significantly more discoveries, filed more patents, and created more innovative products, giving a nice example of how it could enhance human creativity and productivity when paired with expert judgment. The interesting thing to me, though, is that the people benefited the most were the most experienced researchers.

Wasn’t AI a major force in the reduction of the entry barriers to knowledge work? This is still the same technology that led Jensen Huang to tell the world we wouldn’t need to learn programming anymore!

The ever-present work tutor

I want to focus on two works that seem to arrive at the same, opposing conclusion from Toner-Rodgers’. This paper on generative assistants at a call center (from the productivity economics expert Eric Brynjolfsson) and this paper on GitHub’s Copilot impact on developer productivity.

Brynjolfsson’s study explored how an AI-powered conversational assistant helped customer service agents improve their performance. The tool provided real-time suggestions for responding to queries, offering empathetic language tips and links to technical solutions. Researchers observed that newer and less experienced agents benefited the most, significantly boosting their productivity and customer satisfaction scores, as the AI tool disseminated best practices.

Similarly, the analysis on Copilot, an AI programming assistant, assessed the productivity of AI-assisted software developers. They were tasked with building a piece of software and Copilot provided real-time code suggestions and completed repetitive or boilerplate tasks, allowing them to focus on more complex logic. The tool significantly reduced completion time, with novice programmers benefiting the most as it helped them bridge knowledge gaps.

You see the pattern, right? In both studies, the inexperienced people benefit the most from having a language model assist them in their tasks, while the more knowledgeable users didn’t see much of an improvement. This happens because the AI assistants provide small high-value input bits (language tips, code completion) to help achieve a task faster. Moreover, they teach the novices. While there is room for delegation, a language model can also provide inexperienced people with feedback, foster the incorporation of best practices, and help them traverse their learning curves faster.

Perspective is all you need

So, whose paper wins? Does AI help experts or novices the most? The answer is it depends. If we compare the three experiments on the same grounds, we’re performing a small sleight of hands: in all three experiments, humans are using AI, but they are using it differently.

In the case of Toner-Rodgers, researchers used the AI to increase the productivity of their creative process. They delegated the creative burden of coming up with new material combinations in this setup. With each new suggestion, the evaluation became a human task. It was the scientist’s job to use their criteria and their own methods to perform experiments and achieve the task. In this setup, it is expected that those with a more robust criteria and sharper experimental skills, acquired by experience, perform better.

In turn, the analyses of the call center and Copilot feature AI models that foster the most improvements in the least experienced. AI tools in these setups are highly proactive, giving input to the user to help them achieve the task along the whole performance. Having a model give you language tips as you talk or complete your code as you write will achieve the task faster. As opposed to the case of Toner-Rodgers’, the users leveraged the AI input recurrently across the task to meet the expected outcome, filling in knowledge gaps along the way.

Conclusion

The rise of language models in our workplaces has sparked a recurring conversation: Will AI replace us? But framing the question this way oversimplifies the reality. AI isn’t here to compete with human work—it’s here to collaborate with it. These tools are not about outpacing us in a productivity race but rather about enhancing what we can achieve together.

The studies discussed here reveal a more nuanced truth: AI has the potential to empower everyone, regardless of expertise. Whether it’s leveling the playing field for novices or amplifying the abilities of seasoned experts, AI adapts to the task and the user. Brynjolfsson’s work has shown how AI democratizes access to skills, while newer research highlights its role in tackling creative challenges that require human judgment. This is a shift worth celebrating, as it shows AI’s real value lies not in replacing us, but in enabling us to do more.

AI products have been thriving in relieving us from the operational burden in our everyday tasks in the workplace. If in doubt, think when was the last time you wrote an email from scratch. I’m very curious about the tools that will relieve our creative burden: those that will count on us to apply our criteria and expertise to produce new things. For one, AlphaFold is a great example of this framework; I bet Sora and the whole video generation field, which has seen outstanding advances lately, will be another as well. Personally, I’m eager to see what happens when the creative workload comprises a company’s strategy or an education policy draft.